PRODUCTION NOTES

“As for the charges against me, I am unconcerned. I am beyond their timid lying morality and so I am beyond caring.” – Funmilayo Ransom-Kuti

Funmilayo Ransom- Kuti is the motion picture adaptation of the personal story of the Lioness of Lisabi, an esteemed leader in history and an icon, Funmilayo Ransom-Kuti.Based on her autobiography, the rights to tell the story were entrusted exclusively to award- winning director, Bolanle Austen-Peters, this is the first film to tell FRK’s whole story.

The monumental movie chronicles Funmilayo’s extraordinary life journey from her early years as a daunting daddy’s girl chasing her dreams to her life as a teacher, leader and activist.

SYNOPSIS:

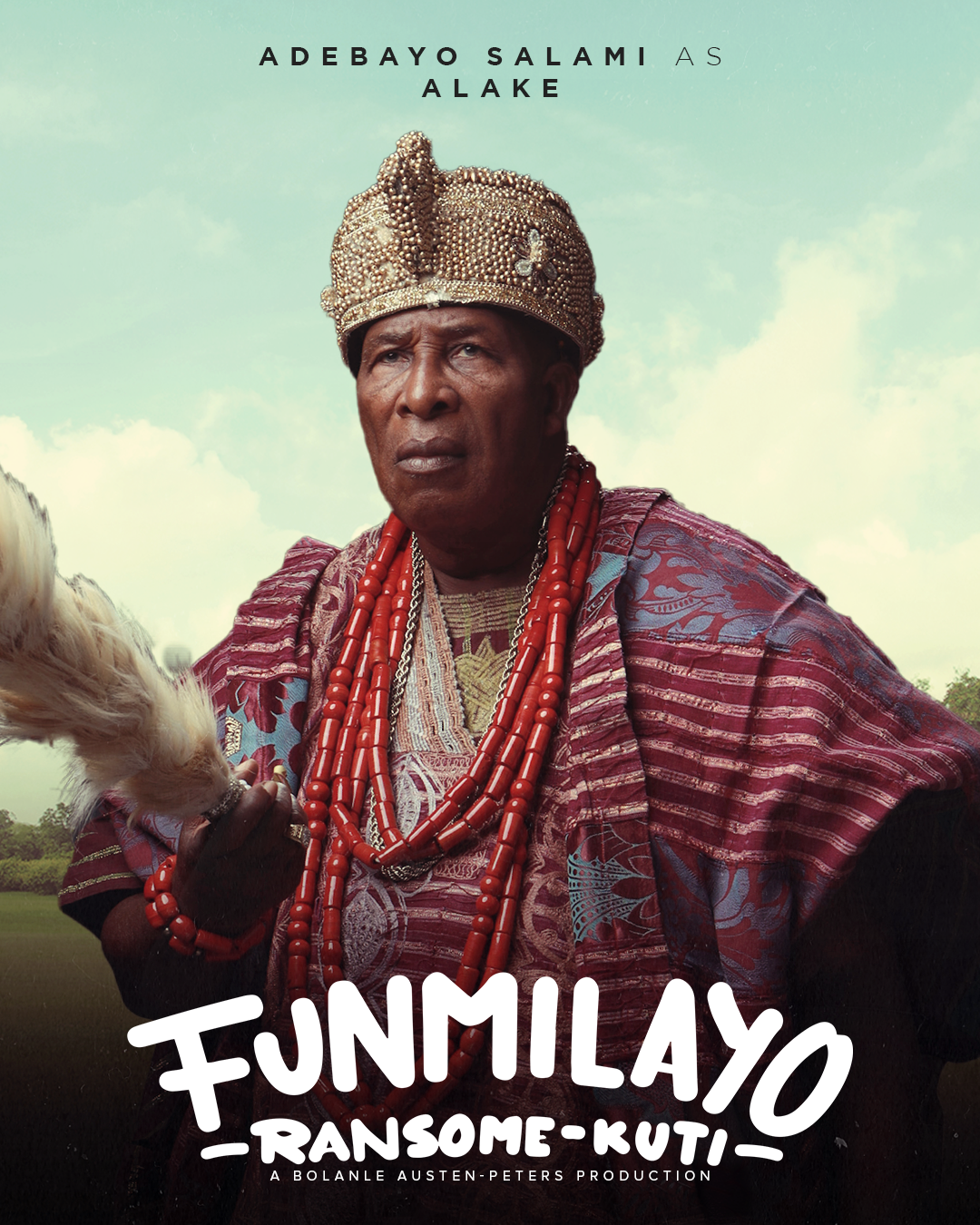

A biopic set between 1900-1950s in Western Nigeria, covers the life of Chief (Mrs) Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, (FRK) (Fela’s Mum) an enigmatic suffragette and activist who blazed a trail through pre-independence Nigeria. She dedicated her life to the struggle for women’s equal rights in Abeokuta and across the nation. FRK is a masterfully told historical epic about how one of the greatest heroines in Nigeria’s history stood strong against economic oppression and gender based marginalization, uniting the market women of Abeokuta towards a joint cause forcing HR Majesty the Alake of Egbaland, to abdicate his throne.

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

It was always going to be a steal to get Funmilayo Ransom-Kuti. Firstly, she’s an icon. Secondly, she comes from a very famous family. There was a lot of interest in getting her story. A lot of film makers wanted to do Funmilayo, but I got it. I got it for various reasons. So I would imagine, having worked on Fela and the Kalakuta queens and the phenomenal success of that play becoming the longest ever running stage play in Nigeria and most successful finding Box Office wise. I’ve enjoyed a beautiful working relationship with the family and having won a couple of awards in movie making as well. I think the family decided to give it to me.

I’m really honored and privileged to be the one. Now, obviously that puts a lot of expectation and pressure on you. I was sure I was not going to do anything mediocre.I also wanted something that the international community would appreciate. I decided to create a film that would travel; local story, but a global audience and global in scale. Due to the fact that we try to tell Nigerian stories that have some form of impact and message. It’s important that we showcase true stories about our heroes and icons that have lived in the past. There’s a tendency for history to forget them, especially in Nigeria. In educating the West, in educating people, it’s important that we tell uniquely African stories that celebrate us as a people and show the strength of character of Africans, especially African women.

For posterity, it’s important that we document stories of our heroes and people who have made a difference in our communities. This is important to change the narrative about Africa and the perception that people have about us as a people.

Women have always played a strong role in community development, family and in nation building in Africa. Yoruba women in particular also have always been traditionally very strong women, both as business women and as political rulers. We’ve always had an Iyalode in government.

We need to start letting the world understand our systems, our community, our political structure and the role of women in our communities. Sometimes, there’s a tendency for people to say, “Ah! You know, women are marginalized.” In Yoruba culture women are not marginalized. Women are strong and they’ve always played a powerful role in governance, in their homes, in raising their families, et cetera, right? That’s correct.

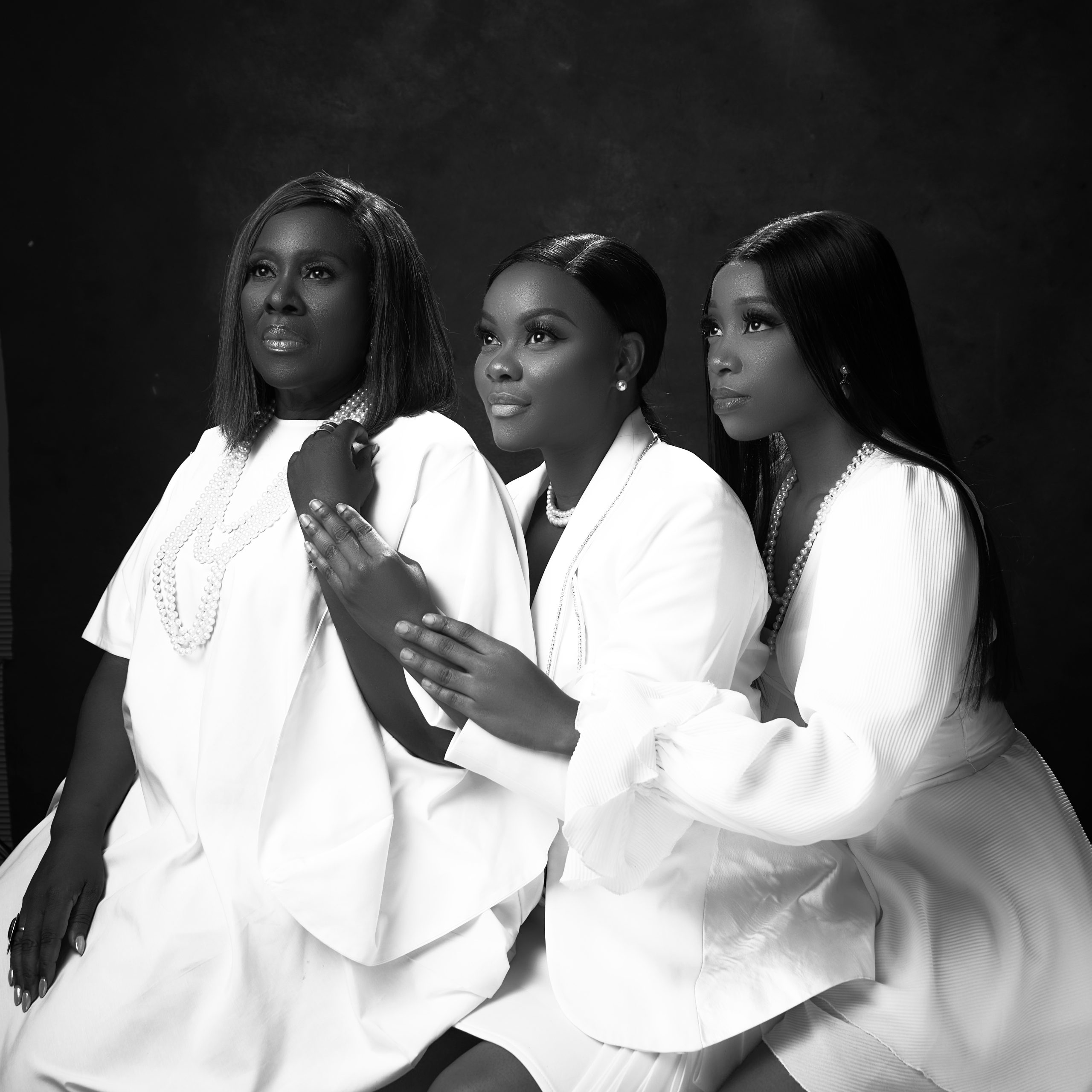

So Funmilayo Ransom-Kuti is a case in point. She worked with other women so there was a strong womanhood and sisterhood going on. In doing this film, what I wanted to portray was the strength of an African woman, how powerful and how diversified our strengths are.

This is a woman who was a political activist, a mother, a wife, a Humanitarian and she still kept her marriage. She confronted colonial and “traditional powers” in the 1950s. This is not something that is new. It happens every day with us. The problem is that we do not document them, so people don’t know. These are the kind of things that we’re trying to bring to the fore, to let people understand that African women are strong, they’re bold, they’re beautiful, and they have so many faces to them, and they cannot be boxed.

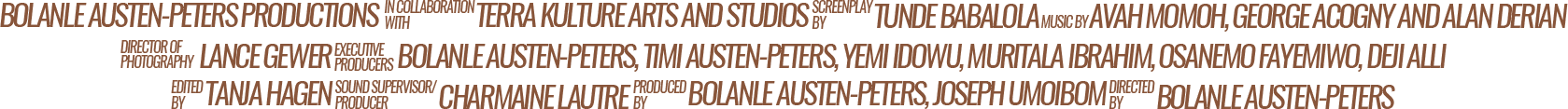

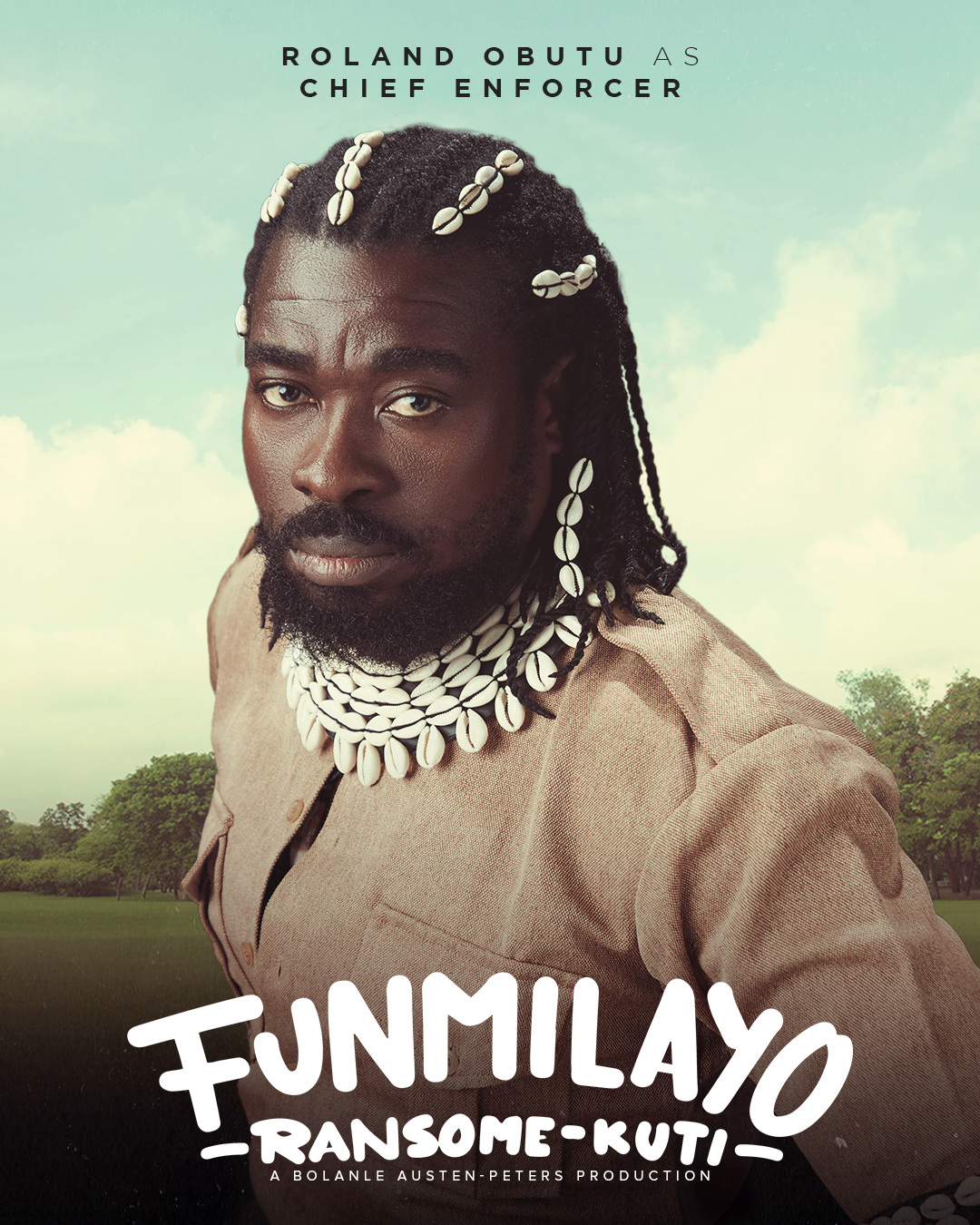

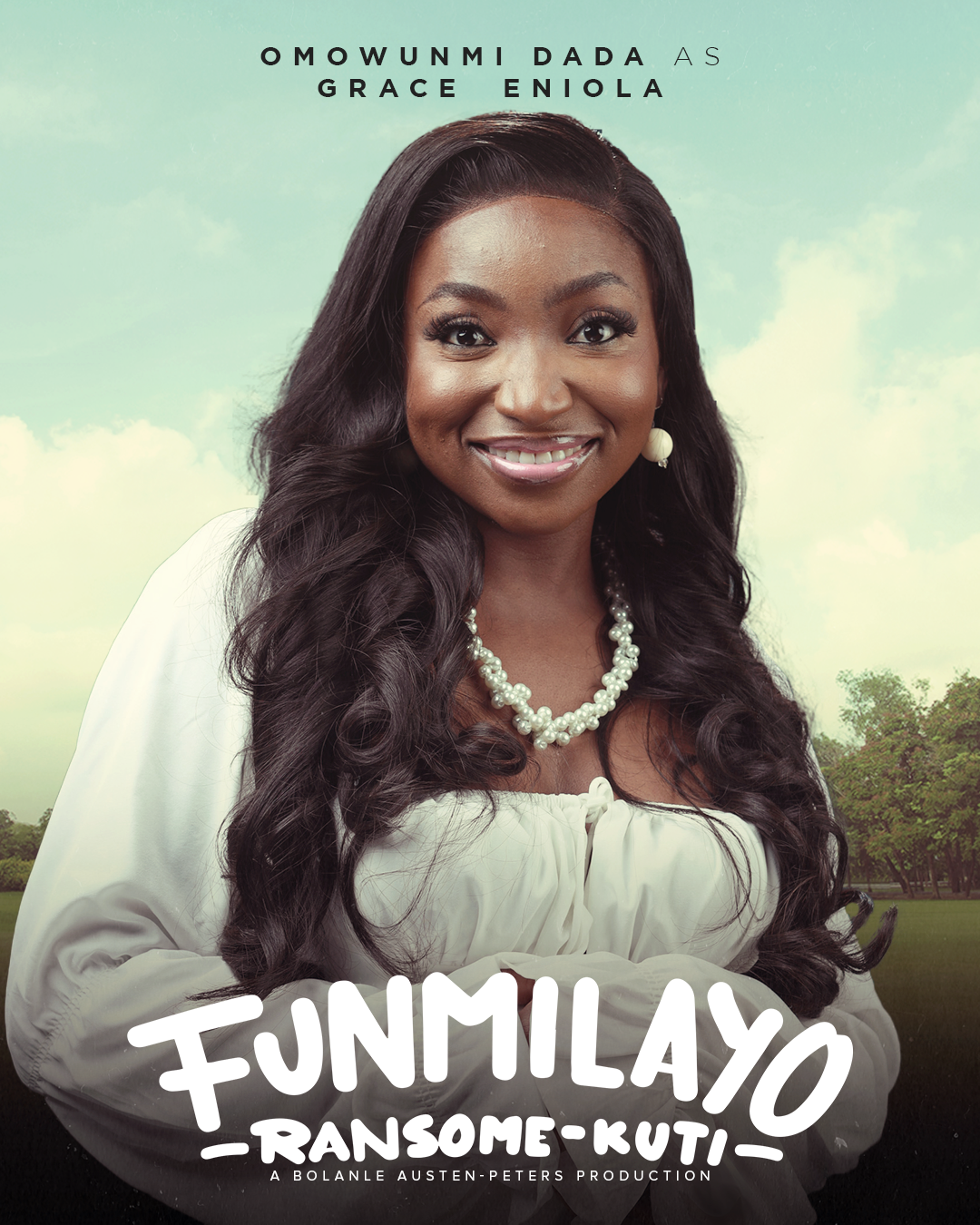

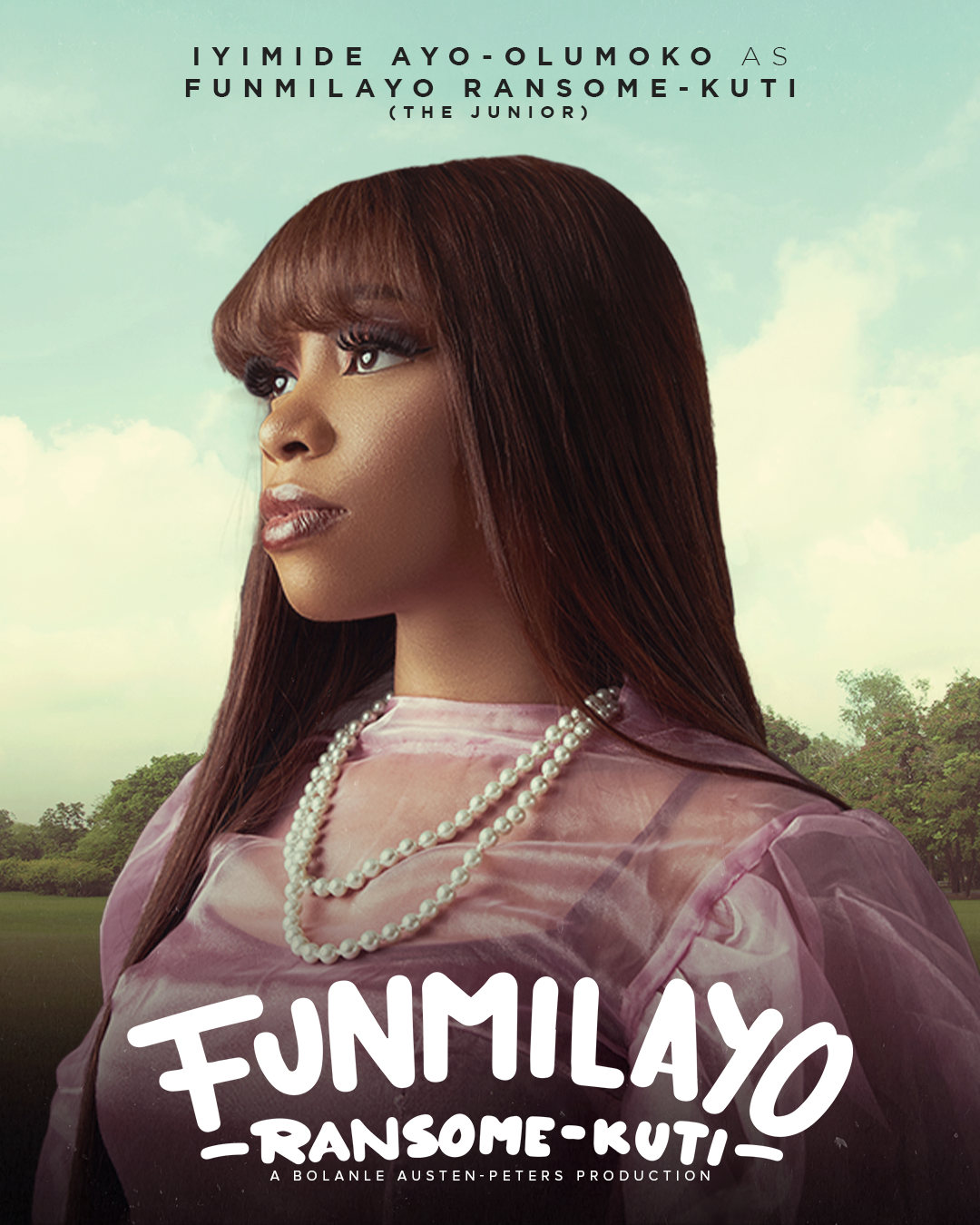

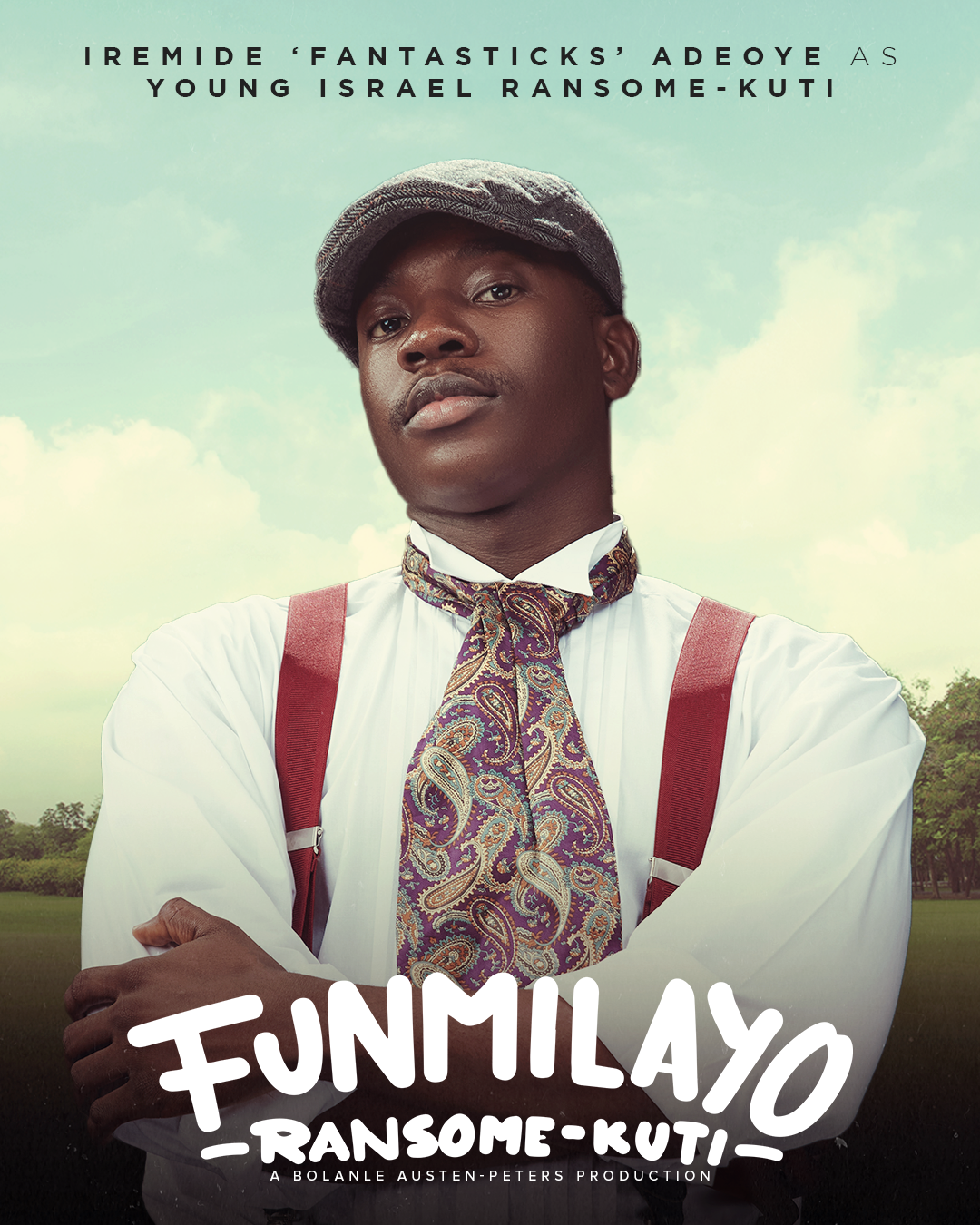

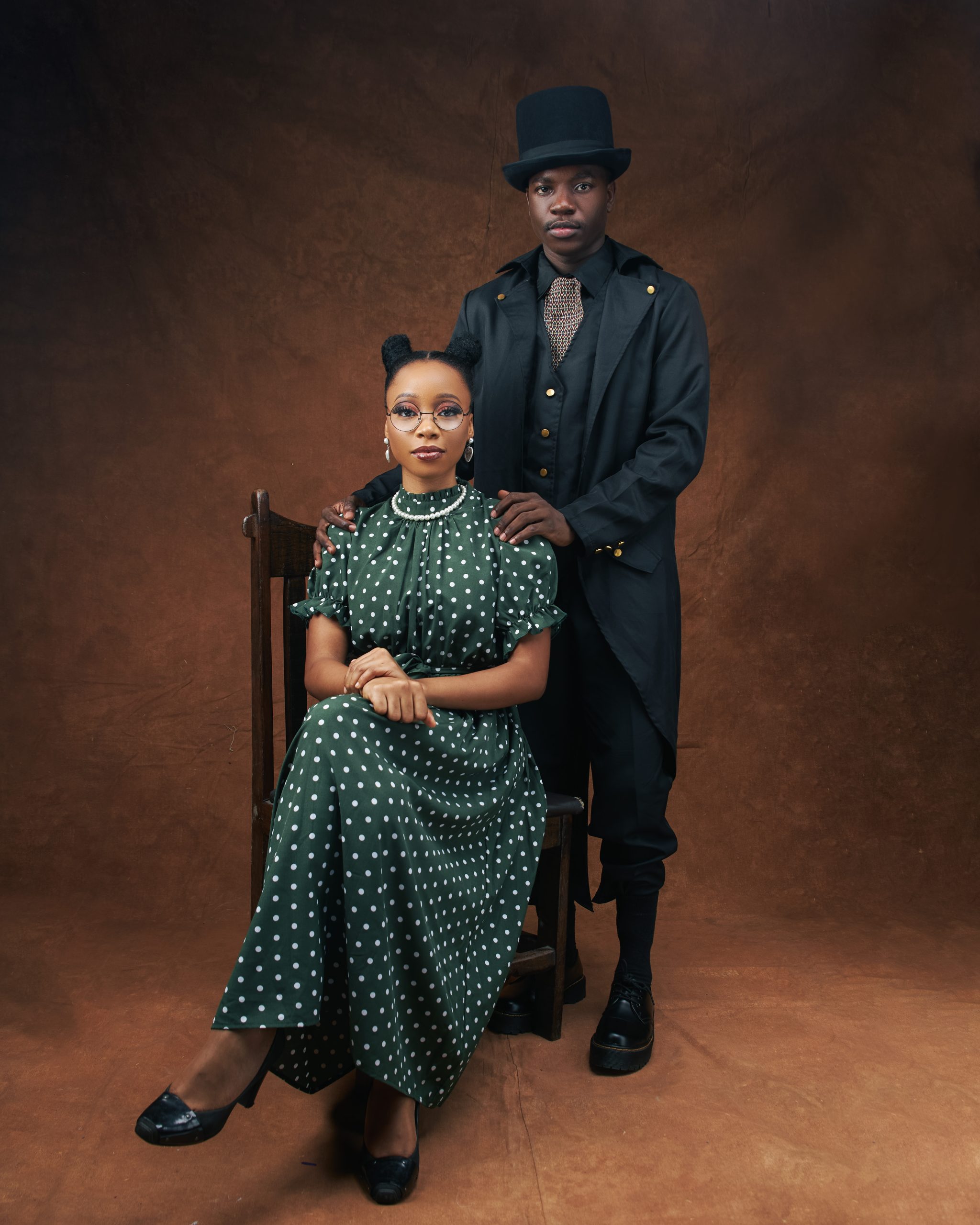

CASTING FOR FRK

GALLERY FOR FRK